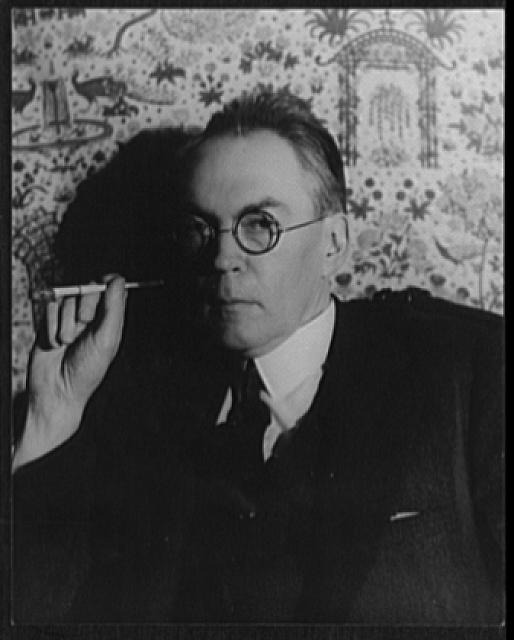

by Dionysius Rogers

Photographer: Carl Van Vechten, 1880-1964

Date Created: 1935 Apr. 30.

Van Vechten Collection, Library of Congress

Do what thou wilt shall the whole of the Law.

James Branch Cabell (1879–1958) was a pioneering American fantasist, widely but briefly appreciated by the reading public. Although it was far from his first, Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice was easily Cabell’s most famous novel. It features the travels of the eponymous pawnbroker as he transacts amorous intrigues with a series of women from myth and fable. The picaresque medieval fantasy of Jurgen includes ample satire kicking against the customary morality of Cabell’s contemporaries. It was first published in 1919, and enjoyed a great deal of fame because of the prompt effort to suppress it undertaken by Anthony Comstock’s New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, then headed by John H. Sumner, who brought an obscenity case against the book. After two years of highly-publicized trial, the court found in favor of the defendants, Cabell and his publisher Robert M. McBride and Company.

In 1921, McBride published a short work by Cabell in hardcover. This book Taboo: A Legend Retold from the Dirghic of Saevius Nicanor was dedicated to Sumner, with the claim that the notoriety conferred by the prosecution had rescued Cabell’s commercial prospects as a writer. He called Sumner a “philanthropic sorcerer” whose “thaumaturgy” had not only generated public interest in Jurgen, but resurrected prospects for the author’s other books.1 The hilarious little story of Taboo is set in the country of Philistia where it is the height of indecency to speak of eating, and a writer named Horvendile is accused of “very shameless mention of a sword and a spear and a staff,” culpable since “one has but to write ‘a fork’ here, in the place of each of these offensive weapons, and the reference to eating is plain.”2

The reissue of Jurgen in 1926 included “A Foreword: Which Asserts Nothing,” to supply an apocryphal fragment of the putative Haulte Histoire de Jurgen in which “a court was held by the Philistines to decide whether or no King Jurgen should be relegated to limbo.”3 In this episode, the tumblebug who is the court prosecutor declares, “You are offensive…because this page has a sword which I choose to say is not a sword. You are lewd because that page has a lance which I prefer to think is not a lance. You are lascivious because yonder page has a staff which I elect to declare is not a staff. And finally, you are indecent for reasons of which a description would be objectionable to me, and which therefore I must decline to reveal to anybody.”4

All of this talk of the symbolic value of weapons seems to emphasize their centrality to the obscenity charge against Jurgen, and to Cabell’s defense. In correspondence with his friend and editor Guy Holt during the course of the trial, Cabell wrote:

I have solved the problem of the Lance ceremony, which is taken from The Equinox, Volume III, pp. 250-258. You have this volume, I know … It is also perhaps of importance that these ceremonies were originally printed in a fifteen cent magazine, The International, which was never arraigned for lewdness; since fifteen cents is considerably less than a dollar and seventy-nine.5

The “Lance ceremony” in question is Chapter 22 of Jurgen, “As to a Veil They Broke,” which takes place in the land of Cocaigne, where “There is no law … save, Do that which seems good to you.”6 The greater part of the chapter is a sentence-for-sentence paraphrase of the first passages of the liturgy of the O.T.O. Gnostic Mass, through the Ceremony of the Opening of the Veil. Cabell did have the original text, as it had been sent to him by Crowley himself.

Crowley first became aware of Cabell when the Virginian author’s philosophical and critical work Beyond Life was sent to him, evidently by H.L. Mencken. Crowley wrote a warm review, which he sent to Cabell before publication, along with a copy of the “All-Drama Number” 3 of volume XII of The International, which included the first publication of Crowley’s “Ecclesieae Gnosticae Canon Missae.”7 After receiving an encouraging reply from Cabell, Crowley’s review of Beyond Life was then published in the same number of The Equinox where he again published the Gnostic Mass.

Crowley also used his review of Beyond Life to mock American Prohibitionism in terms that find their echoes in both Rabelais and Jurgen:

Mr. Cabell … says, “The most prosaic of materialists proclaim that we are all descended from an insane fish, who somehow evolved the idea that it was his duty to live on land, and eventually succeeded in doing it.” Insane fish is right. It is possible that the fish was not insane. It is possible that he discovered that he could not get a drink, except water, and decided to emigrate. If that is insane, I am insane. I hope that Mr. Cabell is insane too, and that I shall meet him in the Solomon Islands.8

The exchange between Crowley and Cabell inaugurated an extensive correspondence. In his Confessions, Crowley wrote, “I have been accused of exaggerated enthusiasm for Cabell,”9 which is small wonder considering he called Cabell “at once the most ambitious, [and] the best worth study, of living authors”10 as well as “undoubtedly the greatest philosopher as well as magician that has ever arisen in America.”11

The Master Therion and Prophet of Thelema believed that a man of Cabell’s sensibility could be won over to champion the New Aeon, and he sent Cabell a copy of The Book of the Law. He wrote, “I am really eager that you should see my point of view, and eventually wake up the world to that superb destiny which lies beneath the superficial sorrow and futility which form the tragedy of your Epic.”12 Cabell was also the addressee of the commentary composed in Cefalu in 1923 and eventually published as “A Memorandum Regarding The Book of the Law,” in which Crowley wrote to Cabell, “The world is waiting for you to utter the wizard-word Thelema.”13 Still hopeful, Crowley addressed a 1942 letter to Cabell with the salutation “Cher maître!”14

Cabell, for his part, continued to show well-informed allusions to occultism throughout his novels, such as the Faustian evocations of The High Place (1923), the solar-phallic theories of religion informing Something About Eve (1927), and the infernal legacies of The Devil’s Own Dear Son (1949). In the essay “The Way of Wizardry” (1924), Cabell described “magicking in suitable estate” as the proper method for authors of fiction, who should burn appropriate perfumes, wear carefully-selected regalia, and decorate their writing chambers according to “high and approved old formulae.”15

Cabell’s books show him to have been a master of such formulae, one justly admired by our

Past Grand Master Baphomet, and deserving of our study and esteem.

Love is the law, love under will.

Note: Significant portions of this nomination essay were originally composed as part II of the paper “Martian Hierophant: Valentine Michael Smith and the New Aeon,” written for the Academia Ordo Templi Orientis conference in Barcelona, June 2018.

- Cabell, Taboo (McBride 1921), 11-13. ↩︎

- Op. cit., 26. ↩︎

- Cabell, Jurgen (Grosset & Dunlap 1927), 3. ↩︎

- Op. cit., 4. ↩︎

- Cabell to Guy Holt, February 16, 1920, in The Letters of James Branch Cabell, ed. Edward Wagenknecht (U of Oklahoma 1975), 31. ↩︎

- Cabell, Jurgen, 157. ↩︎

- The International XII:3, March 1918 (New York, 1917). For the sequence of this correspondence, see Crowley to Cabell, November 7, 1920 (Special Collections and Archives, The James Branch Cabell Library, VCU Libraries). ↩︎

- Crowley, The Equinox III(1), 278-9. ↩︎

- Crowley, Confessions (Arkana 1989), 739. ↩︎

- Crowley, “Another Note on Cabell,” The Reviewer, July 1923. ↩︎

- Crowley, review of Jurgen for The Equinox III(2), O.T.O. Archives. ↩︎

- Crowley to Cabell, September 4, 1923. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Austin. ↩︎

- Published in Crowley, The Revival of Magick and Other Essays (Oriflamme 2, New Falcon and O.T.O. International 1998), 156-161. ↩︎

- Crowley to Cabell, May 24, 1942 (Special Collections and Archives, The James Branch Cabell Library, VCU Libraries). ↩︎

- Cabell, Straws and Prayer-Books (McBride 1924), 74. ↩︎